Warning: Terribly longish post about how a distorted view of beauty creates pain, but well worth, I think, the time to read, as well as the time I spent in ruminating, reading, and interviewing celebrities (the medical and non-medical kind). This work-in-progress is incomplete; I'm still struggling over certain areas. My perspective, of course, is Christian. I welcome yours.Would Prince Charming have kissed Sleeping Beauty if she weren’t, well, a beauty? Would he have singled out Cinderella from across the ballroom if her waist-to-hip ratio weren’t 0.73?

Perhaps not. No matter how much we want it otherwise, beauty is not merely skin deep, particularly for those of us who frantically hop on the beauty treadmill, reconstructing what Mother Nature gave us, fighting to halt the ravages of time—sculpting, buffing, peeling, tattooing, lifting, augmenting, suctioning, plucking. The beauty industry that ranges from fashion to cosmetics, from diet plans to fitness studios, from salons to plastic surgery, grows and thrives on the mindset that physical beauty is the primary standard by which we consciously or unconsciously “categorize” a woman.

Television—the de facto, modern-day arbiter of taste and value—feeds on this need for female beauty. Advertisers capitalize on appearance: even commercials that do not sell or are not in any way related to beauty products portray the wiles and wares of a stunning woman. Cigarettes, beer, cellular phones, bathroom tiles, refrigerators—apparently these gain life and increase in sales only in the hands of a dazzling temptress. According to a U.S. study, more than 5,000 commercials with “attractiveness messages” hypnotize viewers each year. Much of the merchandise marketed exclusively on TV panders to the woman’s desire to look better by peddling near-miraculous beauty and makeover products: topical concoctions that shrink fat, enlarge the bust, and remove scars; Cleopatra foam-tipped springs that, when inserted into the nostril, literally lift the bridge for a perkier nose; and the Chinese growth balls that add inches to height when drank once in the morning and again before bedtime. What’s probably more remarkable is that sales are skyrocketing off the charts.

The public is partly to blame for this frenzy. While height is necessary for our flight attendants to reach overhead bins, we also unashamedly require them to be young and beautiful as they pour our coffee. We tend to listen more to good-looking salesladies, prompting companies to hire them primarily for their looks. Filipino TV viewers perpetuate the vicious cycle: we subconsciously but insidiously demand our performers and broadcasters to look physically appealing even before we determine their level of talent. Even worse, we excuse their lack of talent as long as they are attractive.

The beauty bias is rubbing off on non-celebrities. Plastic surgeons in the Philippines confirm that the openness of a few celebrities about their surgeries has drawn more “ordinary” folk to ask for procedures. They come to the clinic, bearing pictures of celebrities, wanting the nose of Nicole Kidman, desiring Barbie Doll proportions or those of Ethel Booba. (According to plastic surgeon Manny Calayan, the most commonly requested body in the country for the past two years is reportedly Ethel Booba’s—from her augmented breasts to her augmented behind, from the cheekbones etched on her face to the tweaked nose.)

There is no universally accepted ideal of female beauty, lending credence to the adage that beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. David Hume wrote in 1741 that “Beauty is not a quality in things themselves; it merely exists in the mind that contemplates them, and each mind perceives a different beauty.” Some cultures uninfluenced by media find the Rubenesque and Venus de Milo figures delightful, honoring the extra pounds as a sign of prosperity. Generally, however, most women are seduced by catwalk figures: at the height of Cindy Crawford and Claudia Schiffer’s popularity in the 1980s, the prevailing notion was of the robust, healthy woman. Then when the wispy Kate Moss and her scrawny posse crossed the threshold in the 1990s, they ushered in the trend of waif-like proportions (or the lack thereof). So far, this remains the vogue: women in fashion advertisements nowadays tend to be very thin, all the better to fit in the popular low-waist, hip-riding jeans. The average fashion model today reportedly weighs 23 percent less than the average female.

Sometimes women’s search for beauty is about desiring for what they are

not or what they

don’t have. This rather widespread attitude is further cultivated by media and manufacturers; the demand that is created—whether necessary or not—spurs sales. Caucasians, for instance, are persuaded to think brown skin exotic, and they spend much time under the sun and in tanning salons, or purchase tanning lotions to hide their pale skin. On the other hand, Filipinos and other Asians doggedly bow to the hegemony of Western media and yearn for fairer features, turning to papayas, citrus and chemicals to lighten their visage.

Perhaps the more scientific way of determining beauty is measuring the symmetry of a woman’s features or figure, the way that art is similarly studied for symmetry: there is harmony or beauty of form that results from balanced proportions. If, say, a woman’s face were to be folded in the middle and one side laid to rest on the other side, would the points of one part correspond with the other? If yes (as in the case of Jaclyn Smith or Paulina Poriskova), then there is symmetry, hence, beauty. If none, there is an imbalance that is considered unpleasant. This theory at its surface appears reasonable, but it hardly explains why many find Barbra Streisand beautiful despite her hooked nose, why Shannon Doherty used to land plum roles despite her noticeably uneven eyes, or why the distinctive gap between Lauren Hutton’s front teeth does not inordinately bother us so.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with wanting to be beautiful. To gaze at physical beauty gives us pleasure, in the same way that we find pleasure in the beauty of geometric shapes or colors or musical notes. However, to mindlessly clamber onto the beauty bandwagon, subjecting our bodies to immoderate demands, reveals a deeper need that begs to be assuaged.

For many women, physical beauty is more than eye candy: it is a key—to success, perhaps, however one defines success; or to fulfill a biological need; or maybe to obtain affirmation.

Time magazine in 2002 revealed a University of Texas discovery that “ugly people” (the description “ugly” referring to what is considered conventionally unpleasing to the eye) are paid ten percent less than employees with average looks. A similar study pointed out that, all things being equal, employers would hire taller people over those who are shorter.

Laboring under this collective demand for beauty, many celebrity wannabes get a head start on their cosmetic surgeries before they are launched into the world of entertainment. Dr. Vicky Belo reveals that actors are gradually accepting the fact that cosmetic surgery is an “investment in their career,” that their “face is part of [their] job.” Without knowing it, the good doctor echoes what Aristotle said about beauty being “a greater recommendation than any letter of introduction.”

The impact on the professional lives of the “redesigned” celebrities is immediate. Ella of Viva Hot Babes claims that after her bust augmentation, she received more offers to do shows. John Lapus says that after his chin sculpting and liposuction, he’s been receiving compliments from his friends, strangers and even enemies, and his career took off.

The case of World No. 3-ranked tennis star Maria Sharapova further proves that beauty can be a powerful determinant of success in business. Time magazine reported in 2005 that sponsors pay a premium for beauty in tennis and other women’s sports. Hence, Sharapova, with her blonde bombshell looks and trim 6-foot-2-inch frame, rakes in millions of dollars more in endorsements than her equally gifted female colleagues, notwithstanding that any one of these tennis phenoms can easily outplay her for any title.

Still others contend that the longing for beauty is much more primal than a business interest. Evolutionary scientists, including Charles Darwin, say that the dominant notion of beauty can be traced to our biologic need to procreate and is therefore “fundamental to the evolutionary process” of humans (as well as animals, apparently). According to biologists, there is a positive correlation between beauty, on the one hand, and fertility and good health on the other. Beauty acts as a “certification of biological quality,” which purportedly explains why, according to studies, men of diverse backgrounds prefer a low waist-to-hip ratio of 0.6 to 0.8 (meaning, the waist is 60% to 80% the size of the hips), regardless of the woman’s weight. Scientific experiments have apparently shown that a lower waist-to-hip ratio means a higher level of estrogen. More estrogen in the female body results in more reproductive fat on the hips and thighs. Ergo, men will be more attracted to women with an hourglass figure.

While this is an interesting aspect to the hubbub over beauty lust, it does not explain why women obsess about beauty. Childbearing is the farthest thing from the minds of those women who have their double chins removed, or those who permanently curl their eyelashes. The question is, why do we put so much weight on physical presentation?

It seems that we women latch on to beauty to affirm our sense of self; unfortunately, we equate our sense of self with the externals, which is why we rush to comb our fingers through our hair and lick our lips when someone insists on taking our picture (and why we keep only those pictures that show us in our best form), why we’d rather not tell our age, why we submit to the haunting truth in Janis Ian’s song: “I learned the truth at seventeen, that love was meant for beauty queens and high school girls with clear-skinned smiles.”

Many a woman cope with a bad experience by shopping, buying a new pair of shoes, or getting a haircut or a facial—addressing the pain inside mostly with feel-good instant makeovers. After a bad break-up or when a relationship falls apart, some women would get a bust augmentation. For many women, the aesthetic has become an anesthetic. Filipino poet Reuel Aguila recognizes this in his poem,

Pagnanasa (Desire) 2: “From the botox of my face/ To the lipo of my tyan/ Nali-lift ang spirit/ Sa breast kong pina-enhance.” Women feel that physical beauty validates them. Even when women desire to be inconspicuous, there is still the dream of security and acceptance.

Theologians believe that the yearning for beauty finds its root in the curse that God put on the fallen Eve in Genesis 3:16: “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you.” Christian scholars argue that this desire will be inordinate, leading woman to find validation in man, seeking from him what he is not capable of. Andy Comiskey of the Living Waters Ministry argues that the curse upon Eve resulted in woman’s fallen tendency to find her identity in man, to seek completion in him, and mistakenly attempts to discover herself through him. Hence, many women mistakenly adopt men’s notions of female beauty as their guide. Her definition of beauty correlates to his: big breasts, small waist, thin thighs, oval face. Some studies confirm these assumptions. Anders Pape Moller, in his study

Sexual Selection and the Biology of Beauty, presents human evolutionary psychological studies across cultures that reveal “how men rank female [physical] beauty the highest among a long list of attributes, while women rank male resources as the most important attribute of potential mates.” According to Bryn Mawr’s Savithri Ekanayake (

The “Perfect” Female: an Analysis of the Biology of Beauty), studies from around the world found that “while both sexes value appearance, men place more stock in it than women.”

Regrettably, physical beauty is not the real beauty that is the essence of woman—what author Stasi Eldredge calls the “soulish” beauty— the kind that indwells in every woman and does not depend on her outward accoutrements. This kind of beauty takes its moorings from 1 Peter 3:3-4: “Your beauty should not come from outward adornment, such as braided hair and the wearing of gold jewelry and fine clothes. Instead, it should be that of your inner self, the unfading beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit.” Such beauty doesn’t translate to or require an introvert but a heart that is quieted by love and filled with peace, a heart that knows it already possesses beauty.

Eldredge submits that we women seek to unveil beauty within ourselves: deep inside, perhaps even deeper for those who have buried this essence in their hearts, women want to be seen, wanted, pursued and found beautiful and captivating, a beauty that is “core to who we truly are. We want beauty that can be seen; beauty that can be felt; beauty that affects others; a beauty all our own to unveil.”

Perhaps the antidote to the curse on the fallen Eve is to first recognize that woman’s beauty already resides in her from Day One. When God created man and woman, He said that what He had made was “very good.” (Genesis uses the superlative “very”—as in “very good”—only after He made man and woman; in all the other aspects of creation, He said they were “good.”) Creation celebrates woman as the bearer of God’s image, the Imago Dei. Eve was created because things were not right without her; she was not a mere afterthought. Something was not good, and “it [was] not good for the man to be alone.” God calls woman an

ezer kenegdo, a Hebrew term that is difficult to translate: the term

ezer is used only twenty other times in the Old Testament, and in these twenty times,

ezer described God Himself, when He is needed desperately. And when God looked at her, He saw that she was “very good.”

Woman therefore is God’s

piece de resistance. To paraphrase Eldredge: In the crescendo of creation, from formless void to perfection, woman is the beauty to which creation ascends. Only when woman accepts this—that she is the beauty that she already is—can she escape the beauty that ensnares.

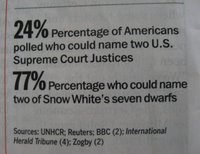

Time Magazine (August 28, 2006 issue) reported there are more Americans who can name off the bat two of Snow White's seven dwarfs than two Supreme Court justices.

Time Magazine (August 28, 2006 issue) reported there are more Americans who can name off the bat two of Snow White's seven dwarfs than two Supreme Court justices.